Types of AIRMETs: Complete Guide on These 3 Conditions

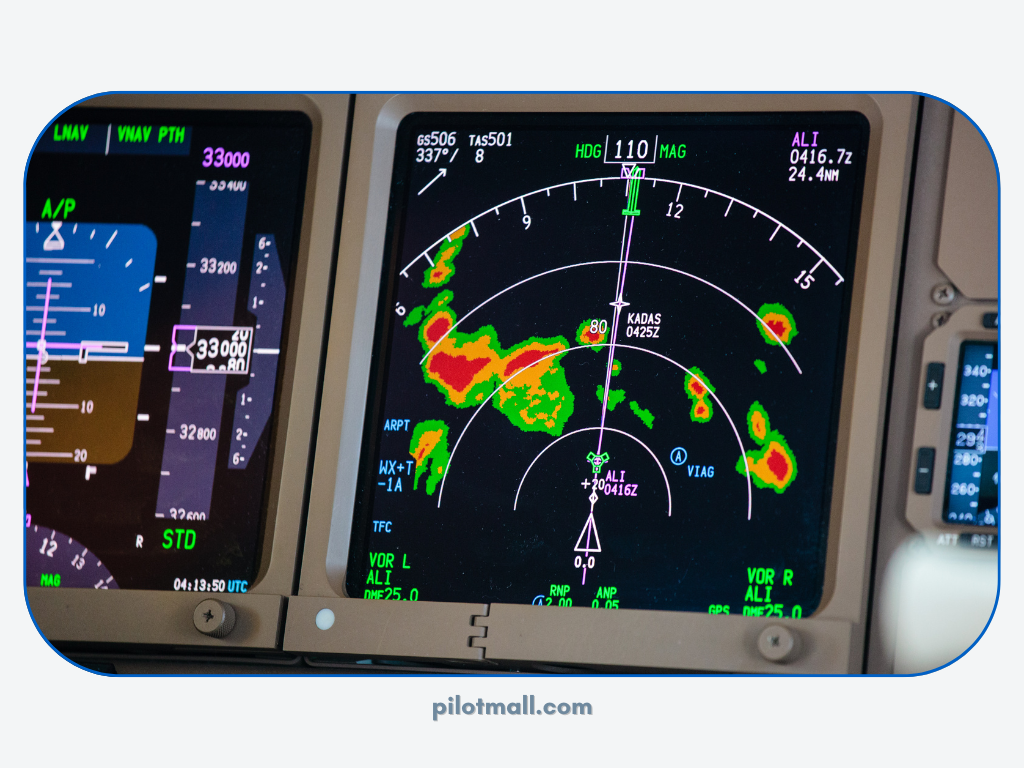

As a responsible human being and pilot, before you commit to a flight, you naturally will want to check the weather. An AIRMET is one of the sources that pilots use to gather the meteorological information needed for flight planning and decision making.

Featured Pilot Gear

Browse our selection of high-quality pilot supplies! Your purchase directly supports our small business and helps us continue sharing valuable aviation content.

As a responsible human being and pilot, before you commit to a flight, you naturally will want to check the weather. An AIRMET is one of the sources that pilots use to gather the meteorological information needed for flight planning and decision making.

What is an AIRMET?

The term AIRMET stands for Airmen’s Meteorological Information. AIRMETs are an inflight weather advisory that informs pilots of the development of weather conditions that have the potential to be hazardous. AIRMETS are issued by the Aviation Weather Center (AWC) based out of Kansas City, Missouri.

The meteorological information in an AIRMET is operationally informative for all aircraft and is especially relevant for light aircraft as the conditions reported in the AIRMET are most likely to cause harm to lighter aircraft. For an AIRMET to be issued, the adverse conditions must have the potential to negatively impact an area of at least 3,000 square miles.

Let's get into understanding AIRMETs and weather phenomena.

Why are AIRMETs issued?

AIRMETs are issued to advise pilots of potentially hazardous and adverse conditions along their flight route. The information in an AIRMET allows pilots to make an informed decision on whether they should continue or modify their flight plan to improve safety.

Conditions that trigger the release of an AIRMET include:

- Icing and freezing levels

- IFR conditions

- Mountain obscuration

- Moderate turbulence

Three types of AIRMETs

AIRMETs divided into the following three types:

- AIRMET Sierra

An AIRMET Sierra is issued for IFR conditions with ceilings of less than 1000’ and/or visibility of under 3 miles over at least 50% of the affected area. An AIRMET Sierra can also be issued to indicate mountain obscuration caused by low visibility.

- AIRMET Tango

An AIRMET Tango is issued when there is moderate turbulence, non-convective low-level wind shear, or sustained surface winds of 30 knots or more.

- AIRMET Zulu

An AIRMET Zulu is issued for moderate icing conditions and freezing levels. When an AIRMET Zulu is in place, there are freezing conditions in the area, so pilots should be alert for icing. Remember that airplane deicing is a crucial step before you take off if you decide to fly in AIRMET Zulu conditions.

Two types of AIRMETs formats

The meteorological information contained in an AIRMET is issued in two different formats. These formats complement each other. They are meant to be used together to help pilots gain ultimate clarity about the impacted areas and timing of the AIRMET’s meteorological events.

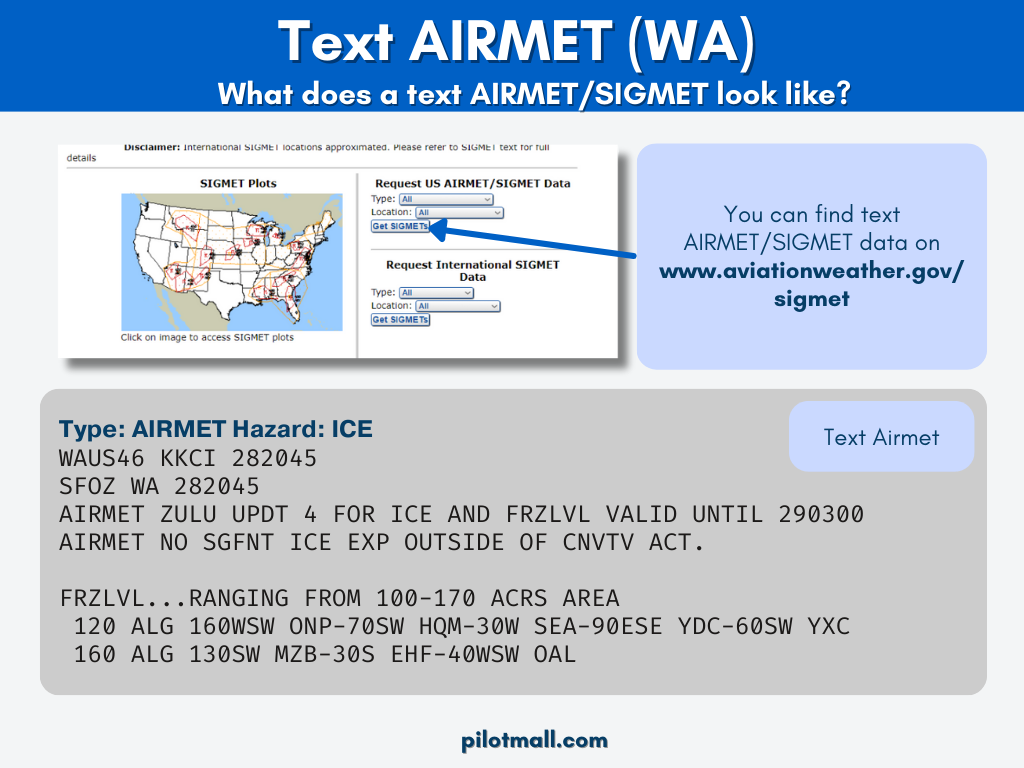

- Text AIRMET (WA)

A text AIRMET is a written version of the AIRMET. It shares the meteorological information in a textual bulletin format. The text version conveys the location of the affected area by relaying its position relative to VORs, however this can be very challenging to visualize from reading it, and the graphical AIRMET takes care of locating the AIRMET on a map anyway.

The main information that pilots should look for in a text AIRMET are the details of what conditions to expect, what altitudes to expect them at, and the expected time frame of development and dissipation details for the event if applicable. Look for these in the text following the string of VOR positioning information.

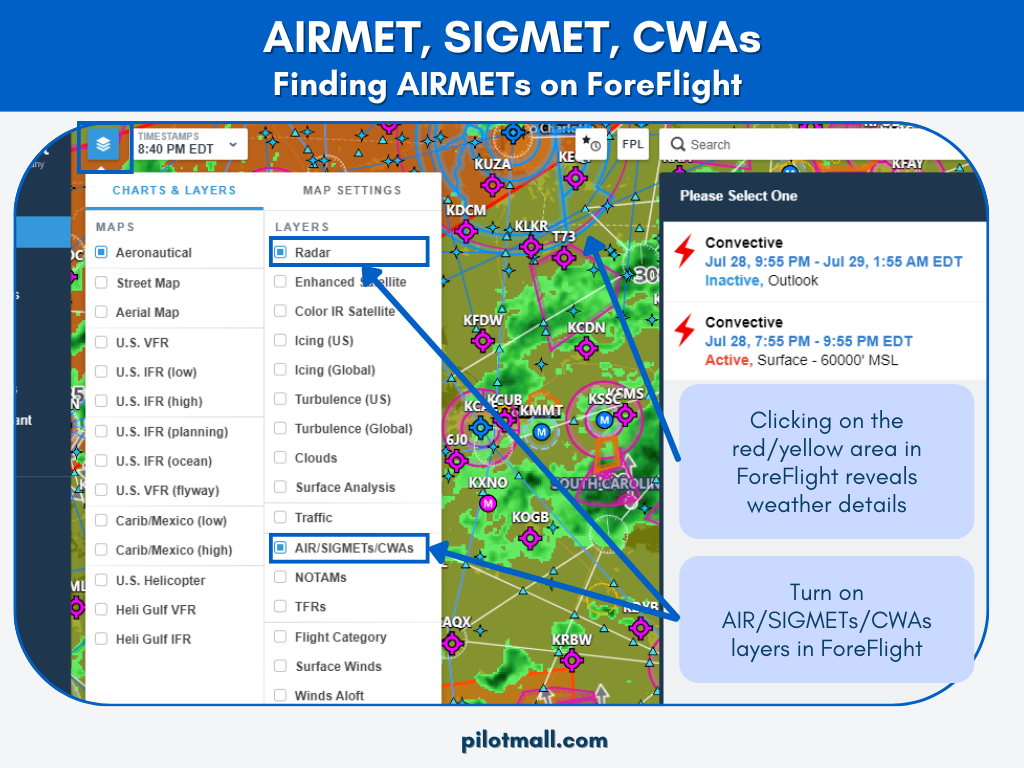

- Graphical AIRMET (G-AIRMET)

A Graphical AIRMET or G-AIRMET is a graphical forecast of weather hazards. It is created by taking the data included in a text AIRMET and translating its information into a visual layer that can be over-layed on a map. This bypasses the need to plot out the location of the AIRMET relayed in the text version.

While text AIRMETs cover a period of 6 hours, the scope of graphical AIRMETs is little different. They cover a period of up to 12 hours and break that span down into 3-hour increments, each with its own graphic overlay.

By viewing each 3-hour snapshot sequentially, pilots gain a clearer understanding of how the significant weather patterns are evolving and moving – both their directionality and speed.

As new inclement weather emerges, one snapshot might show no hazards and the next may show significant hazards. Realize that this indicates the conditions are expected to develop between the time of the first and second snapshot.

When viewing a newly published graphical AIRMET, you will notice that the time periods for the forecast start at the valid time which is 00 hours, then the next snapshot is at +3 hours or 03 hours, the next at +6 or 06 hours, and so on through +12 or 12 hours.

To coordinate the information between the graphical and text AIRMETs, take one of each type that have the same valid, or start time. Hours 00 through 06 on the G-AIRMET will correspond to the information in the text AIRMET. Hours 07 through 12 of the G-AIRMET align with the text bulletin outlook since a text AIRMET for that time frame has not yet been published.

It's important to know how to use an official national weather service. Check the Aviation Weather Center’s Graphical AIRMETs page to view currently active graphical AIRMETs.

Reading a Graphical AIRMET (G-AIRMET)

Each type of hazard indicated by a G-AIRMET is depicted on the map overlay by a unique boundary color and pattern. This is accompanied by brief information on altitude or type of obscuration.

An orange boundary with the turbulence symbol signifies areas of high turbulence. The altitude range where turbulence is expected is given by two numbers stacked atop each other in an orange box.

The top number indicates the maximum altitude of the turbulence and the lower number gives the expected bottom of the turbulence layer, both in hundreds of feet.

Red boundaries with the turbulence symbol are used for low turbulence. Like high turbulence, low turbulence altitudes are displayed stacked in a box matching the color of the boundary line and are listed in hundreds of feet.

Mountain obscurity is communicated using a pink dashed boundary. The cause for the obscurity is coded and listed in a pink box.

Codes include:

- BR (mist)

- CLDS (clouds)

- FG (fog)

- FU (smoke)

- HZ (haze)

- PCPN (precipitation).

A solid purple boundary line signifies areas where IFR is required. The reason for reduced visibility or low ceilings is coded and communicated in a purple box.

Possible codes are:

- BLSN (blowing snow)

- BR (mist)

- FG (fog)

- FU (smoke)

- HZ (haze)

- PCPN (precipitation).

Dark blue boundaries with a dashed line circle indicate icing conditions at the altitude ranges given in the blue box with the top number representing the altitude of the top icing layer.

The bottom can have a single number or two numbers. If a second number is listed, that means that the bottom of the icing layer varies in altitude between the two numbers.

Lighter blue boundaries with zigzags and tick marks show the location of freezing levels, and their altitude can be given as a single number or as a range if freezing is occurring across multiple altitudes.

How often are AIRMETs issued?

- Text AIRMETs are issued every 6 hours beginning at 0245 UTC.

- Graphical AIRMETs are issued every 3 hours and cover a period of up to 12 hours in the future.

- Additional graphical AIRMETs may be inserted in between the standardly scheduled AIRMETs if conditions are changing rapidly and warrant it.

- AIRMETs are terminated by the Aviation Weather Center (AWC) when the condition is no longer present or the time on the AIRMET expires.

- If an AIRMET expires, but its meteorological conditions are still present, the AWC can extend the effective time of the original AIRMET rather than issuing another.

Can I fly in an AIRMET?

The decision of whether or not to fly in an area with an active AIRMET involves many fluid variables and is left up to pilot discretion. This is where your aviation risk management background comes into play.

When making your decision, consider the type of AIRMET that has been issued, your aircraft’s capabilities, your personal level of skill and experience, your preparedness level, and your passengers’ comfort level with inclement conditions.

You may decide to delay your flight, alter your route, or cancel your flight for the day. Weigh all your options and make the best possible decision given the information you have at the time.

One additional thing to take into account is that since the AIRMET is issued for an area of at least 3,000 square miles and over a 6-hour timeframe, conditions can vary at different times and locations within the AIRMET-covered area.

The affected area at any given time may be much smaller than 3,000 square miles. In that case, you might technically decide to fly in an AIRMET, but you could plan your flight to avoid the conditions that generated the AIRMET.

What is the difference between an AIRMET and a SIGMET?

Both AIRMETs and SIGMETs are crucial information for a pilot. An AIRMET is issued for weather conditions that may negatively affect aircraft safety. No convective activity is associated with any of the conditions reported by an AIRMENT.

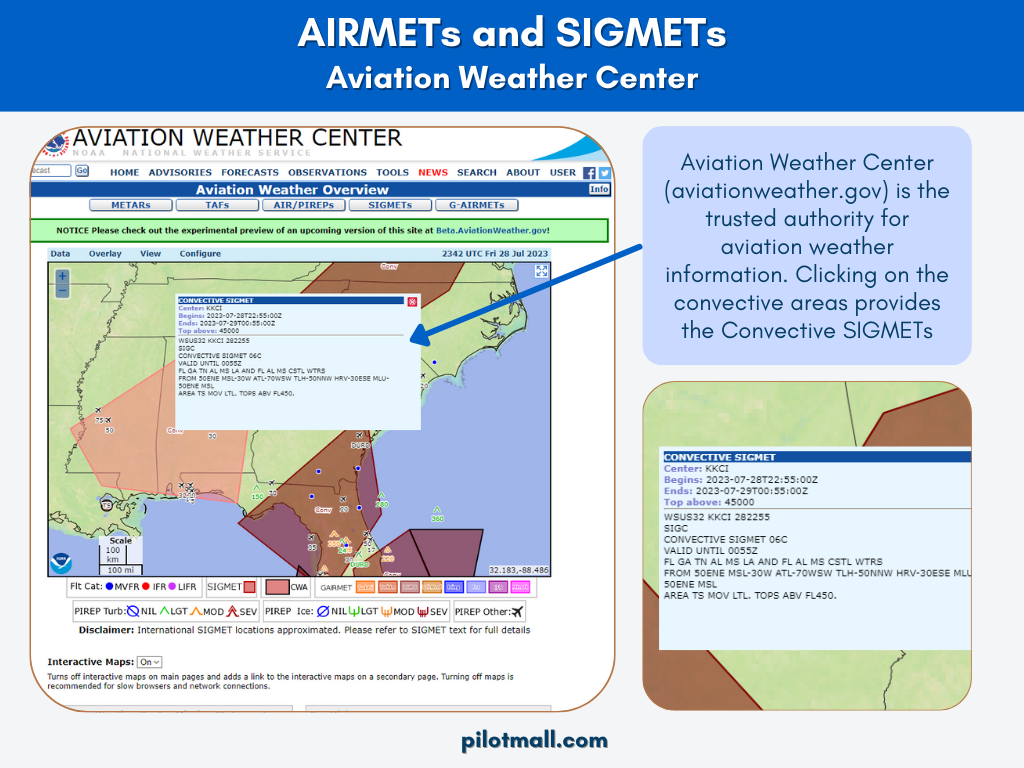

A SIGMET, or Significant Meteorological Information advisory, on the other hand, is issued to indicate severe weather conditions that the Aviation Weather Center has determined will negatively affect all aircraft.

This includes the presence or development possibility of convective activity. Thus, a SIGMET indicates more dangerous conditions than an AIRMET. The standard rule is to always avoid flying in a SIGMET and to carefully consider before flying in an AIRMET.

What is a SIGMET?

A SIGMET warns of any weather conditions, aside from thunderstorms, such as a dust storm, and additional weather phenomena that may be hazardous to aircraft. These advisories are issued (in the United States and its coastal waters) for any of the following potential risks:

- Severe Icing

- Severe or Extreme Turbulence

- Dust storms and/or sand storms lowering visibilities to less than three (3) miles

- Volcanic Ash

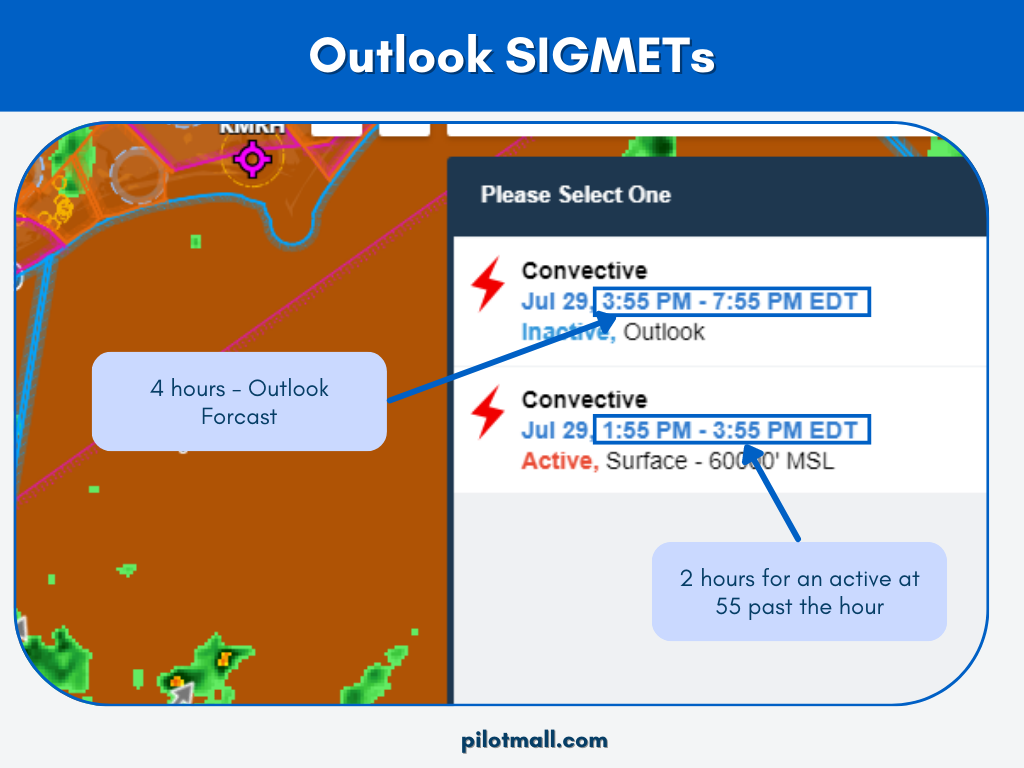

What are Convective SIGMETs?

Convective SIGMETs are issued if these conditions are taking place or expected to take place:

- Line of thunderstorms at least 60 miles long with thunderstorms affecting 40% of its length.

- Area of thunderstorms covering at least 40% of the area concerned and exhibiting a very strong radar reflectivity or a significant satellite or lightning signature.

- Embedded or severe thunderstorms expected to occur for more than 30 minutes.

Special issuance criteria include:

- Tornado

- Hail greater than or equal to 3/4 inches in diameter

- Wind gusts greater than or equal to 50 knots

Mike from Fly8MA explains AIRMETs and SIGMETs including how to read them in his AIRMETs and SIGMETs Explained tutorial.

Takeaways

An AIRMET is like a ground-based weather report advising you of potentially dangerous conditions in the area. Be sure to use an official national weather service source for accurate weather advisories.

Knowing how to read both text and graphical AIRMETs gives you the information you need. As a pilot, it is then up to you to decide what to do with that information. To refresh yourself on some of the concerns and skills of weather flying, pick up a copy of Weather Flying by Robert Buck.

Check out our collection of Weather Flight Training Material.