The 4 Types of Airspeed: How Each Works (Complete Guide)

On the ground, speed is relatively simple to measure, and vehicles like cars only measure one type of speed. Once you take to the air though, other factors like air density and wind come into play and must be accounted for. Accounting for and quantifying the impact of these factors is what led to the definition of the four different types of airspeed.

Featured Pilot Gear

Browse our selection of high-quality pilot supplies! Your purchase directly supports our small business and helps us continue sharing valuable aviation content.

On the ground, speed is relatively simple to measure, and vehicles like cars only measure one type of speed. Once you take to the air though, other factors like air density and wind come into play and must be accounted for and what is displayed on your airspeed indicator isn't always a representation of your true airspeed.

Accounting for and quantifying the impact of these factors is what led to the definition of the four different types of airspeed.

Types of Airspeed

When pilots speak of airspeed, they are referencing one of the following four types:

- Indicated Airspeed (IAS)

- True Airspeed (TAS)

- Groundspeed (GS)

- Calibrated Airspeed (CAS)

It is important to understand how each type of airspeed works including what it measures, how the measurement is done, and how you as a pilot can use that information.

Learn the different speeds on your airspeed indicator in order to understand the safe range to stay within for your specific aircraft.

Indicated Airspeed (IAS)

Indicated airspeed is the measured speed of an airplane as it moves through the air. The IAS is what registers on the cockpit airspeed indicator, and it is based on pressure readings collected by the pitot-static system. The IAS is inversely correlated with the true airspeed based on altitude.

If true airspeed remains constant, and the only variable to change is the aircraft’s altitude, at a higher altitude, the air is thinner and there are fewer molecules to enter the pitot tube and create pressure. The airspeed indicator gauge will register a lower indicated airspeed.

At a lower altitude, the air is denser, and the increase in molecules causes a higher pitot pressure which will translate to a higher indicated airspeed.

The indicated airspeed as displayed on your airspeed indicator gauge in knots of indicated airspeed (KIAS) is used for aircraft speed limits, speed changes, and ATC speed restrictions. The published v-speeds for each aircraft are also relayed in indicated airspeed.

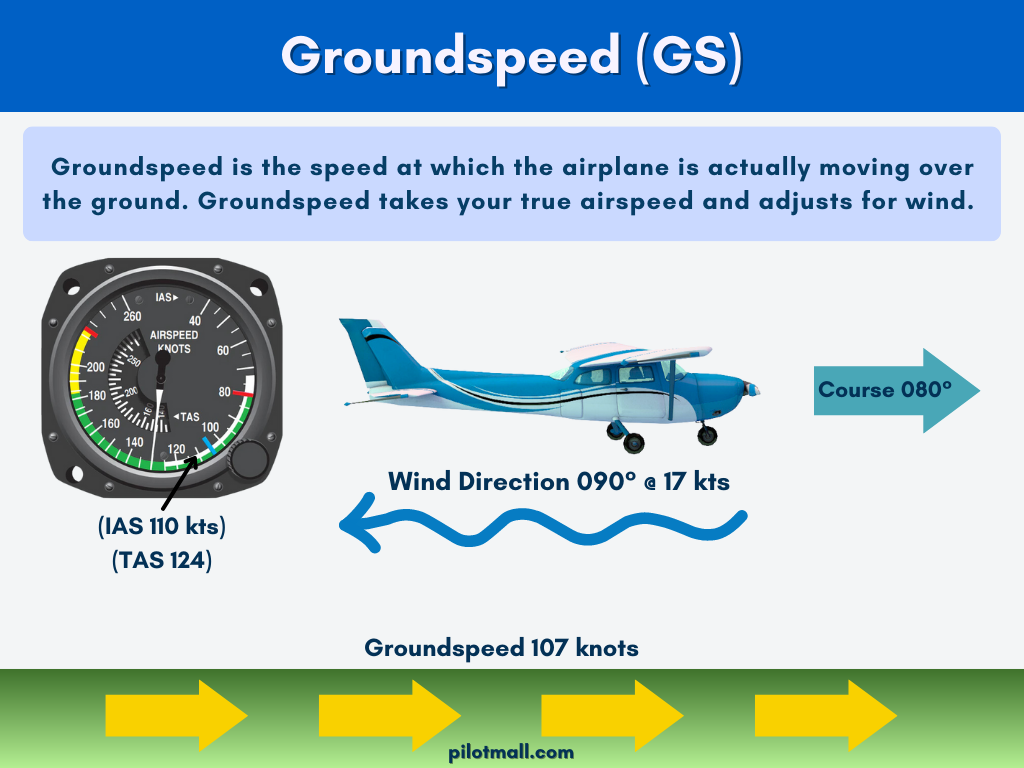

Groundspeed (GS)

Groundspeed is the speed at which the airplane is actually moving over the ground. Groundspeed takes your true airspeed and adjusts for wind.

A tailwind pushes the plane faster relative to the ground than to the airmass, so the ground speed would be higher than the true airspeed.

A headwind slows the plane’s forward progress relative to the ground while increasing its speed relative to the airmass, so the groundspeed would be lower than the true airspeed.

Ground speed is used by pilots when making time and distance calculations.

True Airspeed (TAS)

True airspeed TAS is the speed the airplane moves at in relation to the air mass it is flying through. If the air is perfectly still and the aircraft is flying straight and level, the true airspeed will be the same as groundspeed.

True airspeed TAS is calculated by taking the indicated airspeed and adjusting for pressure and temperature variables.

If the airplane is flying into a headwind, the true airspeed will be higher than groundspeed. This is because the plane and the air mass are moving in opposite directions, so they pass each other more rapidly and the pitot tube reads a higher pressure and therefore a higher true airspeed.

The inverse is true with a tailwind. In this case, the true airspeed will be less than groundspeed because the air mass is moving with the airplane, so the relative speed between the plane and the air is less than it is between the air and a stationary point on the ground.

True airspeed is also impacted by altitude. At higher altitudes, with less dense air, the aerodynamic drag on the plane decreases and the true airspeed increases. The rate of increase is 2% per thousand feet.

Pilots use true airspeed in knots (KTAS) for performance measurements and flight planning.

Calibrated Airspeed (CAS)

Calibrated airspeed takes the indicated airspeed (IAS) and then corrects for known instrumentation or position errors.

For example, in a perfect scenario, the air flowing into the pitot tube would be unaffected by airflow from other parts of the aircraft. It would be receiving and measuring free flowing air.

Unfortunately, this is simply not always the case. By the time air enters the pitot tube, it may have sped up or slowed down as it moved around the airfoil, or experienced skin friction.

The angle of attack or flap setting could also have interfered with and altered the reading. This is why we have calibrated airspeed.

The calibrated airspeed takes the aircraft specific known value of the calibrated airspeed offset for each aircraft and applies it to the indicated airspeed reading. The calibrated airspeed offset is defined by the manufacturer and posted in the pilot operating handbook (POH).

Calibrated airspeed is usually only a few knots different from indicated airspeed, with the most significant variations occurring at slower airspeeds, lower altitudes, and in nose-up attitudes.

When flying at slow speeds, is important to realize that your aircraft stall speed is based on indicated airspeed (IAS), and that depending on the variables, it could stall at a higher calibrated airspeed.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Which airspeed is shown on my dashboard?

- The speed shown on the gauge in your cockpit is the Indicated Airspeed (IAS). This is the direct reading from the pitot-static system without corrections for temperature or altitude.

- Why does Indicated Airspeed decrease at higher altitudes?

- At higher altitudes, the air is less dense (fewer air molecules). This results in less pressure entering the pitot tube, causing the instrument to indicate a speed lower than the aircraft's actual speed through the air (True Airspeed).

- What is the difference between Groundspeed and True Airspeed?

- True Airspeed (TAS) is how fast you are moving through the air mass. Groundspeed (GS) is how fast you are moving across the ground. The difference between the two is caused by the wind (headwind or tailwind).

- When is Calibrated Airspeed most important?

- Calibrated Airspeed (CAS) is most critical at low speeds and high angles of attack, such as during landing or slow flight, where installation errors and position errors of the pitot tube are most pronounced.

Take Away

Understanding airspeed is essential for pilots, as it profoundly influences the process of creating a flight plan. Whether it involves determining fuel efficiency, assessing groundspeed, or navigating diverse conditions, accurate airspeed comprehension is crucial.

It enables safe and efficient flights, guiding route decisions and ensuring a smooth journey for all on board.

So, fellow aviators, embrace the beauty of the skies while prioritizing safety – your expertise in airspeed will be your wings to adventure!

Want to learn about Airspeed?

Check out our articles related to Airspeed!

- How it Works: Airspeed Indicator (Extensive Guide)

- Pitot-Static System: How does it work?

- How to Calculate True Airspeed and What It Is (Guide)

- Aircraft Vertical Speed Indicator (VSI): How Does it Work?

- Watch Your Attitude: A Complete Guide to Aircraft Attitude Indicators

- Understanding the Slow Flight Technique